Look.

Look at this.

Here is some more.

Do you see?

Do you see?

Look at this.

Do you understand?

Do you?

DO YOU?!

Look.

Look at this.

Here is some more.

Do you see?

Do you see?

Look at this.

Do you understand?

Do you?

DO YOU?!

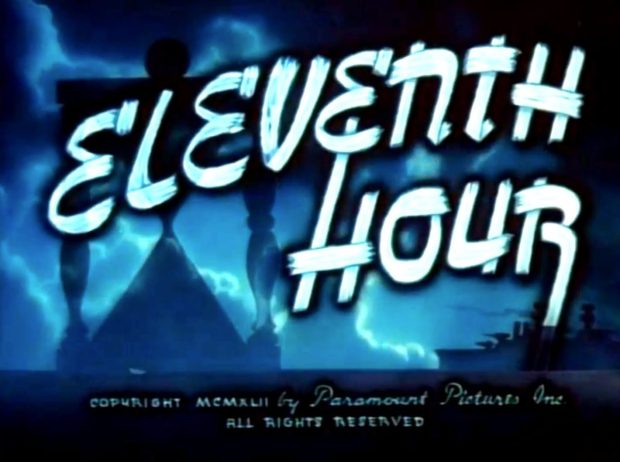

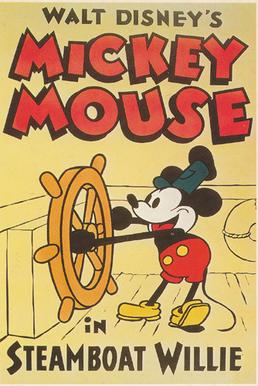

Seven years is not that long a time. Seven years ago we got the first of the Star Trek reboot movies, Michael Jackson died and Jay Z and Alicia Keyes released Empire State of Mind. Not exactly ancient history. Go back and watch Steamboat Willie. Now watch Music Land released by Disney a mere seven years later.

So what the hell, right? How did we get from that to that in a mere seven years?

When talking about Steamboat Willie it’s almost more important to talk about what it’s not than what it is, as so many myths have sprung up about these seven minutes of animation. So, for the record Steamboat Willie is not:

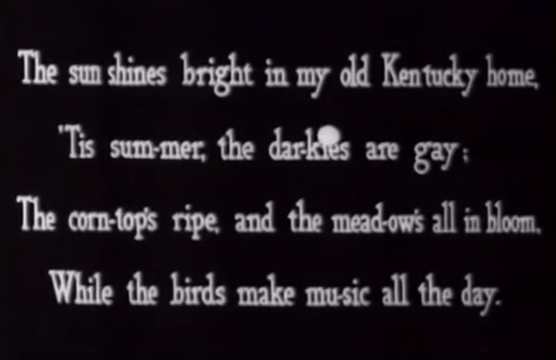

Willie’s real claim to fame is a little less sexy. It’s the first cartoon to use fully integrated sound and visuals, where the sound and pictures were recorded on the same film. There were other cartoons that used sound and music before this, but that basically involved playing the movie and the music on two separate tracks and hoping that they’d keep in sync like Wizard of Oz and Dark Side of the Moon. It doesn’t sound like it should make a huge difference but it really does. Take a look at Inkwell’s My Old Kentucky Home from 1926.

Wow, second sentence. You are so out of date in so many different ways that its almost impressive.

Now take a look at Steamboat Willie.

If you ever want to earn yourself some serious animation nerd cred, the next time someone asks you who your favourite animator is, fix them with a steely gaze, whisper the words “Winsor McCay”, drop the mike and then moonwalk out of the room.

I carry a mike around with me at all times for just such an eventuality.

McCay is not a household name, but he is almost certainly one of the greatest animators of all time, one of the two most influential animators of all time and most amazingly of all, possibly the first animator of all time. Okay, obviously, we will never know who was actually the first animator. Probably the first kid in class who realised that with a little doodling in the edges of your copybook you could make it look like your teacher was being eaten by velociraptors. But to start this decade by decade look at animated shorts I need a big, flashy, incandescent Big Bang and by God, McCay fits the bill.

McCay was a celebrated cartoonist probably most famous for the Little Nemo comic strip, which combined incredible detail with gorgeous, trippy surrealism.

Inspired by the flip books that his son brought home one day, he decided to create an animated version of Little Nemo, drawing four thousand rice paper cels by hand and pioneering many animation techniques on the fly, all while carrying on with his regular comic strip work. That’s right. He virtually invented modern animation. He did it single-handedly. And he did it in his spare time. Today’s short is Winsor McCay, the Famous Cartoonist of the N.Y. Herald and His Moving Comics and because it’s public domain and up on You Tube, we can all watch it together. Great, right? We never do stuff together any more.

So the movie begins before animation has been invented which is why it’s in live action (joking, joking, I know about Blackton and Cohl, I can read Wikipedia too). Winsor McKay is betting his fellow artists that he can create a comic strip that moves. And can I just point out how insanely lucrative newspapers used to be? Those tony-looking motherfuckers with their fancy suits and monocles and brandy and cigars aren’t newspaper owners, they aren’t even journalists. They are COMIC STRIP ARTISTS. That’s how much money was in the newspaper business in the nineteen tens. I mean, look at these guys! They don’t look like artists, they look like the guys who owned the fleets that hunted the blue whale to the brink of extinction! Anyway, they of course scoff and mock his idea and presumably tell him to try something more sensible like circumnavigating the globe in eighty days. This is a recurring plot in McCay’s cartoons incidentally, which could be titled Watch My Idiot Friends Lose Money by Betting Against Me, Winsor Goddamn McKcay.

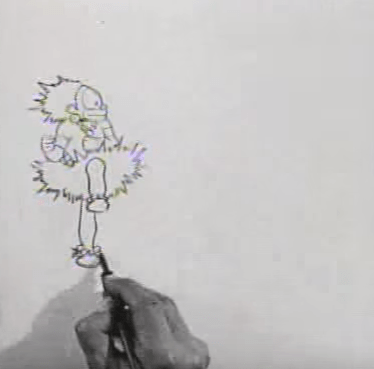

Undeterred, McCay draws one of his characters, the Little Imp, to show his friends how this whole “animation” thing is going to work.

“I shall begin with racism, gentlemen, as this is 1911 after all.”

“Of course!”

“Quite right.”

One of the things you notice watching the live action scenes is that compared to a modern film the pacing is absolutely glacial. When McCay draws Little Imp, you see him draw the entire thing from start to finish, no cuts, no edits. We’re talking about a period where film is so new and exciting that even watching something as mundane as a man drawing a picture is fascinating in and of itself. You’d watch it because you most likely had never seen that before. Anyway, McCay bets his friends that he will draw 4,000 images in one month and make them move. I especially love the moment where one of McCay’s friends tries to leave and he literally pushes him back down in his chair.

“Oh, I’m sorry, is my INVENTING A NEW ARTFORM BORING YOU SIT YOUR ASS DOWN!”

We now get a sequence of delivery men bringing barrels of ink and massive slabs of paper to McCay’s office and I honestly don’t know if that’s supposed to be a joke or an accurate representation of the material that was required. McCay directs them as they bring it while wearing a fedora and smoking a cigar like a goddamn Ink Mobster. There’s some pretty unfunny business with Winsor’s son knocking over a huge pile of papers and the middle of the film drags pretty hard once you’ve gotten over the culture shock of watching people from over a century ago. But at last, McCay unveils his animation. And it is…

“No words. Should have sent a poet.”

Chuck Jones described Winsor McCay thusly, as if the first living creature to emerge on Earth was Albert Einstein, and the next was an amoeba. He’s like the Antikythera mechanism, something that should not exist as early in history as it does. He’s the first to do this, or close enough, so he doesn’t know what you’re not supposed to be able to do. He doesn’t know that you have to keep the character models simple. He doesn’t know that you’re supposed to keep the perspective unchanged and flat. When he swings the “camera” around to show an incredible, meticulously detailed dragon from the side, the front and then the rear before it slouches off into the distance he doesn’t know that you’re not supposed to be able to do that. There is no story, not really. It’s simply characters coming to life and exulting in their existence and creating new characters to play with. It’s dreamlike, and surreal, and moves with a grace and fluidity that most animators living today will never be able to match. The Titanic was being built when Winsor McCay created this, single handed. It wouldn’t be until the eve of the Second World War that Walt Disney, with a team of dozens of the most talented animators in the world and a budget of over a million dollars, would be able to create animation that rivals it. It’s beautiful. It’s amazing. It breaks my goddamn heart.

Jones went on to say that the two most important names in animation were Walt Disney and Winsor McCay and that he honestly didn’t know whose name should go first. Walt himself might have bowed out of that contest. When McCay’s son visited the Disney studios in the fifties Walt gave him the tour and told him “Bob, all this should be your father’s.”

***

Unshaved Mouse has been shortlisted for best Film and TV blog at the Blog Awards Ireland 2016. Please click on the link below to vote for Mouse!