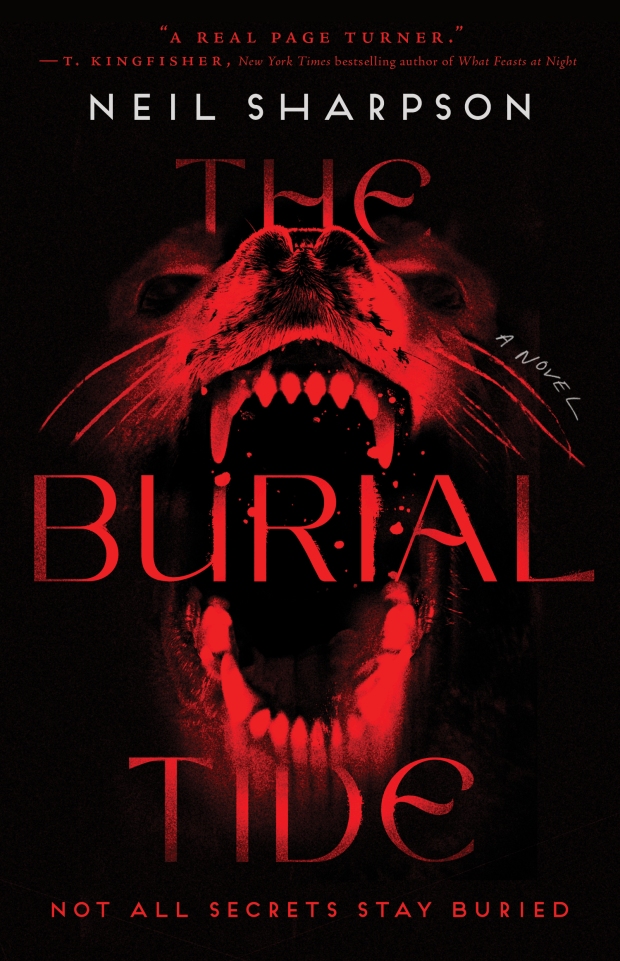

We’re a mere two days out from the launch of my next novel, The Burial Tide. This is a story I loved working on, partially because it allowed me to indulge my love of world-building. And early draft of the novel contained passages from fictional books and newspapers that established some of the history of Inishbannock, the fictional Kerry island where the story takes place. Ultimately, it was decided to cut these for pacing but I didn’t want to let them go to waste. So please, enjoy these early, blog-exclusive glimpes of the world of The Burial Tide.

The 1930s saw the commission, now with full government backing, embark on its most sustained and intensive period of folklore collection. With a staff of six full time collectors, armed with cumbersome Ediphone recorders, the commission was able to collect an estimated 100,000 pages worth of folktales, songs, stories, poems and proverbs from every county in the nation, preserving much of the vernacular culture that was in danger of being lost with every passing decade. Support for the commission’s work was enthusiastic amongst the general public, and collectors often reported being embarrassed by the generosity and hospitality of the villages they visited. There were difficulties, however. Many informants, the more elderly in particular, were uncomfortable with being recorded by the Ediphone and their submissions had to be transcribed by hand, which added greatly to the workload of the collector. And, while a warm welcome was common, it was not guaranteed. Many of the more isolated, tight-knit communities, particularly in the west of the country, were suspicious and sometimes even hostile to these strangers from Dublin. One of the commission’s most respected collectors, Professor Seán Mac Gearrán, made repeated visits to the isle of Inishbannock, off the coast of County Kerry, hoping to interview the island’s inhabitants. Mac Gearrán’s letters to commission director Séamus O’Duilearga during this period are telling. Normally unfailingly upbeat, Mac Gearrán’s account describes the islanders as “churlish” and “dour”, complaining to his superior “you would think I was an Englishman from their disdain for my person”.

His last letter to the commission, dated 12 April 1938, informs them that he had finally convinced one of the islanders, the landlady of the local tavern, to be interviewed. From his time in Co Kerry, Mac Gearrán knew many of the strange and macabre stories that the mainlanders had of the island, and was anxious to hear the islanders’ own account.

What MacGearrán recorded is unfortunately lost to us. MacGearrán (and his Ediphone) sank on the boat back to the mainland within sight of Dingle harbour.

MacGearrán’s loss was a terrible blow to the morale of the commission, to a degree that is still visible. In the lobby of the Irish Folklore Commission (now the Department of Folklore in UCD) hangs a great map of Ireland which the commission used to track the presence of their collectors throughout the country. If one looks closely in the bottom right corner they will see a tiny island of the coast of Co. Kerry. There, drawn in blue pen, is a small cross and the following words in the large, loose hand of Seamus O’Duilearga:

Inishbannock- Noli Intrare.

Anna Bale, A History of the Irish Folklore Commission. Béaloideas Press 2002.

***

In a year when the Irish renewables industry has been facing severe headwinds, the opening of the new Inishbannock Offshore Windfarm has been seen as a much needed victory. Phase 1 of the project will be completed at the end of the year with infrastructure and the first turbine (Windmill One, 120 metres) already operating off the west coast of the island. Phase 2, if approved, will commence work next year and will expand the total number of turbines to forty, making it one of the largest wind farms in the country.

While opposition from local landowners to windfarms has been increasing in recent years, the Inishbannock Wind Farm has faced no such difficulty.

“Support from the local community has been fantastic” says project overseer Cian Morley. “Everyone understands how important this project is, to the local community, to the country and to the planet.”

Local businesswoman Gráinne Dunne, proprietor of the island pub, agrees: “Inishbannock has survived, unlike so many other island communities, because we’re willing to adapt. The windfarm will bring employment, investment and opportunity to the island.”

When asked if there was anyone on the island who disagreed with this assessment, this reporter was told that I was “welcome to ask around.”

True enough, if anyone on the island opposes the project I was unable to find them.

“Island Community Blow Away by New Wind Farm- The Kerry Leader.”

I actually got my copy yesterday. I choose to believe that my local bookstore is staffed by absent-minded time travelers, not that they made a mistake and handed it to me before the shelf date.

Planning to start reading it tonight, thanks for the bonus material, I’m looking forward to it. Always good to read something spooky around this season.

Lemme know!