This review was requested by patron Alex Hu. If you’d like me to review a movie, please consider supporting my Patreon.

Fuck Wikipedia.

I had one hell of an intro lined up for this one. I was going to open with a description of the Book of Kells, and detail how the blue dye illustrating this mediaeval masterpiece of Irish art had to be imported all the way from ancient Afghanistan. I would then tie that into a line from The Breadwinner where the character Nurullah describes how the ancient peoples of Afghanistan traded all over the world. Then I was going to connect that to how director Nora Twomey’s previous film The Secret of Kells led directly into The Breadwinner, showing how Ireland and Afghanistan have, improbably, been transmitting ideas and beauty between each other for millennia. And how even between two incredibly distant nations there can be bonds of shared history and culture. How we are all, truly, one people.

And then I go to Wikipedia and discover that the theory of the Book of Kells being created with ink from Afghanistan has been debunked so never fucking mind then.

“Don’t know why I bother really.”

Anyway, this is the third film of current animated hotness Cartoon Saloon. Like their previous two movies, this is an international co-production, this time between Ireland, Canada and Luxembourg.

“I helped!”

“Aw, you sure did.”

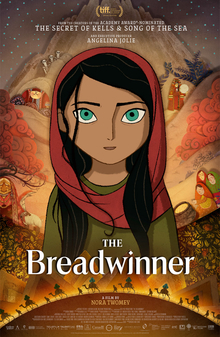

Directed by Nora Twomey and produced by Angelina Jolie, The Breadwinner is based on the novel by the same name by Deborah Ellis. Upon the movie’s release in 2017 it was heralded as an instant classic and became the only non-American film to be nominated for Best Animated Feature in 2017.

Boss Baby was also nominated. Because the Oscars are meaningless nonsense.

But is it really that good? Does it really deserve to be spoken of in the same breath as classics like Boss Baby and Ferdinand (seriously, fuck the Oscars)? Let’s take a look at The Breadwinner or, as I call it, Mulan but Everything is Terrible.

The movie opens in Afghanistan in 2001 where Nurullah, a former teacher who lost his leg in the Afghan Soviet war, is running a stall in the marketplace with his young daughter Parvana. Nurullah makes now makes his living writing and reading for people, as most can’t thanks to the Taliban’s somewhat retrograde education policies.

“Yeah, but it’s a golden age the Professional Literate. May it never end.”

Nurullah also hawks items to make ends meet, including a beautiful child’s dress which Parvana sullenly notes she never even got to wear. Parvana yells at a passing dog who’s been sniffing around her dress and this draws the attention of a young Taliban firebrand named Idrees and an older man named Razaq who’s also in the Taliban but is one of the cool ones who isn’t all judgey about it.

That’s Razaq on the right by the way, not Nurullah though they look so similar I thought they were supposed to be twins. I’m guessing that it’s intentional because Razaq does become something of a father figure to Parvana so they wanted to have him resemble her actual father but it kinda feels lazy. Then again, they’re both Afghan men in their forties at a time when they have to have long beards and covered heads so maybe there’s only so much they could have done to visually differentiate them.

Idrees demands to know why Parvana is out in public making noises like a human and tells Nurullah that she is old enough to be married and also tells him that he (Idrees) is looking for a wife which has got to be the most fucked up marriage proposal in history. Nurullah tells Idrees that Parvana is already betrothed and takes her home. Parvana asks her father if she’s actually going to be married and he says “kid, you’re 11.”

He says he wants Parvana to spend her time playing and telling stories and she says she’s too old for that now because, as Eglantine Price once told us, 11 is the Age of Not Believing.

They come home to where the rest of the family (mother Fattema, sister Soroya and baby Zaki) are preparing dinner. Parvana bickers with Soroya over not getting enough water from the well.

Now, because I’m completely clueless, the first time I saw this I thought that because Parvana and Nurullah were so much darker than Fattema and Soroya that they were actually different ethnicities, and that maybe, I dunno, Parvana was Nurullah’s child from a first marriage or something. It was only afterwards that I realised “oh shit, they’re darker because they’re the half of the family that’s actually allowed out in sunlight” and I got reeeeeeeal depressed.

Anyway, despite living in the outer boroughs of Hell, the family is happy and loving. But when Parvana teases her sister over her mole, Nurullah orders her to apologise and she refuses. Suddenly there a hammering at the door and the Taliban arrive, led by Idrees. Idrees tells them that Nurullah has been teaching women how to read and he’s dragged away to prison.

And suddenly our story is a survival horror. Three women. Trapped in their house. With no adult male relative to escort them outside.

And the food is running out.

At first the family hold out hope that Nurullah will be released after a few days. Parvana tries to distract Zaki by telling him a story about a young boy who ventured into the mountains to recover magic seeds that had been stolen by the evil Elephant King (insert GOP joke here). These sequences are animated in a much more brightly coloured style and are interspersed throughout the whole movie. My guess is that these sequences were included to stop the movie being so overwhelmingly bleak. But the problem with that is, well, we’ll get to that.

So after a few days pass, Fattema decides that there’s nothing for it but to go to the prison and beg for Nurullah’s release. On the way she gets discovered by one of the Taliban who demands to know what she’s doing outside unescorted. She tells him that she’s trying to get her husband out of jail and shows him a photograph of Nurullah and the Taliban guy just beats her.

He just beats her for like five minutes. It’s awful and brutal and terrifying. And one of the most terrifying things about it is that the guy doing the beating is clearing freaking out and doesn’t even really understand why he’s doing it. He’s just acting out a script that’s been plugged into his head.

Parvana helps her mother limp back home and the situation looks dire.

It’s at this point that Parvana decides…

Actually, scratch that. What I really like about this scene is that it’s not really clear whose idea it is that Parvana has to disguise herself as a boy. Parvana goes and cuts her hair in the mirror, and Soroya then gently takes the scissors and cuts her hair until it’s short enough for her to pass as a boy. It’s all done wordlessly and it’s left ambigous as to who is actually is coming up with The Plan. Soroya? Parvana? Or both at the same time?

Parvana dresses in some clothes belonging to her dead brother Sulayman, and goes to the market to buy water and food. Parvana exults in the freedom being a boy brings her, and is able to win bread for her family like some kind…of…bread…winning…provider! That’s the word I was looking for.

She also discovers that Kabul has something a thriving drag scene when she meets Shauzia, another girl who’s disguised herself as a boy as she tries to make enough money to escape her abusive father oh what a fun little romp this movie is. Shauzia helps Parvana get some paying gigs to go towards a bribe to get her father out of jail.

She also sets up her father’s old stall and reads and writes for customers while also selling off her old clothes. She sells her red dress to an old man, telling him it will look lovely on his daughter, only for him to reply curtly “she’s my wife”.

Razaq shows up and doesn’t recognise Parvana, and asks her to read a letter for him. This scene is just beautiful.

Parvana sits in the shadow of this huge man who peels an apple while she reads. We don’t see his face, but as she reads and he realises that the letter is telling him that his wife is dead, he slowly stops peeling.

Heartbreaking moment, beautifully rendered.

Razaq slumps off in shock but comes back a few days later to pay Parvana for reading the letter for him. Parvana asks Razaq if he can do anything to save her father and he gives her the name of his cousin who works in the prison.

Meanwhile, Fattema has written to her relatives, promising Soroya in marriage to a cousin if they can get her and her entire family out of Dodge (the old Pashto name for Kabul).

Parvana and Shauzia are meanwhile working in a mine under the supervision of some Taliban, including Idrees. He recognises Parvana and tries to kill her but at the last minute he gets dragged away because it’s October 2001 which means “Knock Knock?” “Who’s there?” “NATO”.

“I just hope all those years of terrorising cripples and small children have prepared me to face the full might of the Coalition Forces.”

Parvana runs home and Fattema tells her to get her things because they’re going off to live with their family in Mazar-i-Sharif (the Venice of Northern Afghanistan). Parvana refuses to leave Nurullah behind and runs to the prison.

Fattemah’s cousin arrives and demands that they get in the car so he can take them to Mazar-i-Sharif and Fattemah says that they can’t leave without her son and he’s all “we can’t wait!” and they’re all “why?” and he’s all “are you crazy? Don’t you know what’s going on?! Have you been living in one darkened room completely cut off from the outside world?!” and they’re all “Yes” and he’s all “Well, good. That’s how we roll.”

He starts to hustle them into the car and Fattemah screams that they can’t leave her daughter which causes the Cousin to snap “Son?! Daughter?! Which is it?!”

“My child is non-binary, you have a problem with that?”

“Obviously! LOOK AT MY HAT!”

At the prison, everything’s going all Attica up in here as the Taliban round up all those prisoners who are able to fight and kill those who can’t. Parvana sees Razaq and begs him to rescue her father. Finally recognising her, he promises to do what he can and tells her to wait outside the prison. To keep herself from panicking as the guns fire and jets scream overhead, Parvana tells herself the story of the boy and how he finally confronted the Elephant King.

The boy came to face to face with the Elephant King and told him: “My name is Sulayman! My mother is a writer. My father is a teacher. And my sisters always fight each other. One day, I found a toy on the street. I picked it up. It exploded.

I don’t remember what happened after that because it was the end.”

This device, of a character within the movie telling a story that runs parallel to the main plot, is pretty common in animated films and The Breadwinner finally made me realise something: I hate this device.

Typically it goes like this, a character tells a story that mirrors the actual events of the movie with both coming together for a dual climax. I don’t like it because it’s inherently redundant. You’re taking twice the time to tell one story. And that’s when it’s done right.

Here…Parvana’s story is just there. It’s just another story within the story that doesn’t have any thematic or narrative parallel with the main story (unless I’m being incredibly dense which is absolutely possible). I have no idea what the Elephant King is supposed to represent. Parvana’s Fear? War? The Taliban? A Republican Party still in the thrall of the neo-conservative wing? Elephants? It’s just a big threatening thing that suddenly stops being big and threatening because…I have no idea.

The visuals and the performance almost carry this but the more I thought about this scene the more I think it falls completely flat. There’s really no narrative connection between Parvana waiting outside the prison for her father to arrive or and Sulayman confronting the Elephant King other than that they both happen at the same part of the movie. So Sulayman’s confrontation with the Elephant King has to work as a climax in its own right and it doesn’t. What was needed here was a devastating reveal that would cast everything we’d seen in a new light.

In this scene we learn two things:

1) Parvana based the hero of her story on her brother.

2) Sulayman died when he picked up a toy in the middle of the road that was actually an IED.

1) doesn’t work as a reveal because who the fuck else is the hero going to be based on, Hamid Kharzai? And 2) doesn’t work because we already knew that Sulayman was dead and this is just explaining how he died. It’s not revelation, it’s elaboration. It doesn’t matter if he was blown up by an IED, shot or had a severe allergic reaction to a peanut. That’s just a detail. The devastating part is that he died, and we already knew that. Now, if we learned that he died saving Parvana, or something like that, something that changes the emotional calculus for us…but that’s not what we get.

So this is the conclusion of the story of the Boy and the Elephant king and it’s ultimately a big nothing. So what about the actual climax of the movie, Parvana rescuing her father? Does that work?

Honestly, no.

Maybe it works better in the novel where we get a better insight into Parvana’s emotional state but in a movie it’s kind of hard to get around the fact that our hero saves the day by…waiting outside a building while a secondary character actually does the heroing. And look, I’m not saying I wanted to see Parvana storming the prison with an AK-47 but it kind of rankles that this story of female empowerment finishes with the heroine being reduced to a helpless onlooker. Anyway, Razaq rescues Nurullah (who is now half dead with starvation) and puts him in a wheelbarrow for Parvana to take home.

As they flee Kabul, the Cousin’s car breaks down. Fattemah decides that she can’t leave Parvana behind and she faces down the Cousin while Sororya escapes with Zaki. Fattemah’s determination terrifies the Cousin, who thinks she’s mad, and he flees without her.

And the movie ends with Parvana’s family made whole again, and an exhortation from the poet Rumi:

“Raise your words, not your voice. It is rain that makes the flowers grow, not thunder.”

***

File it under one of those movies that I respect more than love. It’s beautifully animated and full of atmosphere, but also rather rote in its story choices and walks up to the line of being emotionally manipulative at times. An excellent movie, but falls short of all-time classic status.

Animation: 18/20

Goes for a more realistic style than Kells or Song of the Sea and renders Afghanistan in a far more realistic fashion than those films versions of Ireland. Unfortunately, Afghanistan is bleak as balls.

Leads: 15/20

Saara Chaudry gives a beautiful, understated performance as Parvana.

Villain: 16/20

Wanted to kick his ass. In a good way.

Supporting Characters: 15/20

Well written, engaging characrers let down by some repetitive character designs.

Music: 18/20

Mychael Danna’s score is gorgeously evocative.

FINAL SCORE: 82%

NEXT UPDATE: 28 February 2019

NEXT TIME: I sense a great disturbance in the Force…

I really wanted to like this movie more, but yeah it’s not as captivating as Kells and Song were. Still very pretty.

Sweet, Star Wars. The prequel era isn’t my favorite, but I seem to recall that miniseries being pretty good.

Hey guess what, the Frozen 2 teaser is out!

Everyone seems to have taken a level in badass. I sure hope there’s a threatening villain in this one, because unleashing that much concentrated awesome on someone like Hans would be like sandblasting a saltine.

I must do a write up

Can’t wait to hear your thoughts

That would be great! Predictions about the plot too mouse, the more incorrect the more hilarious in hidsight and you look like a genius if you right. Will Tudyk play his old character or some new one?

It all depends on Tudyk’s lae

I am now really excited for the 28th.

I really like this movie. I can completely understand the criticisms you’ve brought forward, but I would still put this in the love category.

Ah Genndy Tartakovsky’s Star Wars. You know looking back at his previous series “Samurai Jack” I’m constantly amazed at how much story he was able to tell through facial expressions alone.

Now this sounds like an interesting movie, having grown up at the height of the “America! Fuck Yeah!” era. I think it’s important to see these kind of movies or read stories like “The Kite Runner” or “Persepolis” to see the common, everyday people that so easily get grouped together with the “terrorists” or “people of a dangerous culture” that happens so easily both in fiction and the real world.

Now it may just be me, but I got kind of a “only the dead are without fear” vibe from the climax of the story of the boy and the elephant king. Why shouldn’t such a small child be able to face down a fearsome beast? He can’t be hurt by such things anymore.

But I may be wrong in that regards, I haven’t seen this movie yet.

I suspect that the point of the stories is to show that under all this terribleness, there is a rich culture which got supressed in senseless violence. Something to hold onto.

But I agree. I actually didn’t manage to finish the movie, I was so bored by it, because it was so predicable, and I felt manipulated by it, too. I applaud the attempt, but I think there was the need for something there…like, if the main character would actually use all those stories the way Sara uses her imagination in the The Little Princess, as some sort of source of hope, with her imagining herself in the role of the heroine. That might have worked. As it is, it is a story which should have been around 30 to 40 minutes long stretched out until it got unbearable.

I really enjoyed this movie. Not in a “really respect what they’re doing” was, although I do. I enjoyed watching it. Not as much as the other Studio Saloon movies but still. Then again I enjoy a lot of bleak and depressing things as well as existing purely to disagree with you.

Thanks for reviewing this film!

I’m in the minority it seems in that this is my favorite of the three Cartoon Saloon films and the only one that I really like a lot. I’ve had problems really getting into the other two films. I dunno if this one is easier for me because I am a Muslim, I can identify with a lot in the story and that it’s cool to see Muslim characters in an animated film.

Anyway, I do love the animation and story of this. And yeah, I did think the climax and ending didn’t quite work 100% and I wish we saw what happened afterwards, but I’m still pleased overall.

I love what this film does showing how an extremist terrorist group can destroy a society and how our enemies are only a minority of individuals, not a whole ethnic or religious group as a whole.

On another note, what are your thoughts on the ‘Frozen 2’ teaser?

Pending

Thanks for the review! 😄

When I red the description of your planned beginning of this post I thought it sounded kind of sappy at first, but then I remembered how good you are as a writer so the finished thing would have been amazing.

I am not a fan of story with a story myself. It’s often used as an exuse to have more creative and fantasy type animation (and maybe keep kids entertained and hammer the moral home to them). I tried to google to find good examples of it in case I am forgetting a good example but could not find others but only could find narrators and stories that actually happened in the story as examples so maybe I need a better search term.

Am I the only one a bit bothered by that nobody involved in directing or writing the film or the book is nowhere near the region or from the culture of the heritage? And I didn’t notice consultants either. There days films like form Disney get heavily critized even when it’s fantasy films and with consultants (even Moana form the types of Lindsay Ellis) and nobody has issued with this even though it’s not fantasy but story set close to modern day? I assumed prior the writer was form Afghanistan and it was just animated in Ireland the way Persepolis was form an Iranian writer.

Most of the cast are of Afghan extraction I believe, and I know the author interviewed many Afghan women for the book.

Holy shit. I… I remember this book! I *liked* this book! There’s a movie?!

I’ve got to go and round up all my sisters and cousins who read this.

There is indeed.

I think that the story-within-a-story here is actually a subversion of what we expect from these kinds of heroic character arcs. In some ways we also expect too much of our characters in this kind of setting or story. We think that a hero is defined by their success or fulfillment in the face of horrible circumstances, but isn’t that rather condescending? If we told a story with the kind of climax we expect from most stories, is it to inspire the people in question or just to inspire us, the posh western consumers? Really, telling such a story to a Taliban victim also carries connotations of “see, it’s your fault. You didn’t want it enough. You didn’t try enough. You weren’t brave enough. You weren’t creative enough.”

The victory of this story does have its starting place in the bravery and will of the main character, but it isn’t merely bravery and will that gives her victory. She is not in control of her world, and her will and strength alone cannot save her. Instead, it is her human grief resonating with her enemy that saves her. Razaq is Taliban, albeit a more temperate member, and he has suffered grief from the hands of his own community. Parvana treats his grief with dignity and sympathy, which makes him bond with her and become willing to help her in a way that hurts himself. It is not right or realistic to have Parvana charge into a prison that is systematically killing off its tenants, nor is it fair to demand that of her. That within her enemy there is an mutual experience of love and loss is what saves her. While I agree that the Elephant King story has a forced ending, it is essentially implied that the tragedy and grief of Sulayman’s character is what disarms the elephant in that story. At the end, the moon (which represents the love and grief Razaq had for his wife, who was named “moon”) shines down upon all the characters at play, as it is love and grief that unites them.

The climax of this story robs its viewers of the ability to vicariously believe they can defeat their enemies through will and strength –an ego-centric victory. But that is not the only kind of victory that can be achieved. Sometimes real victories are made through the more tragic channels that then create empathy. I come from a more right-wing community with a harder stance on LGTBQ issues. The places where I have seen my community soften on those issues does not come from LGTBQ advocates asserting their will, but from stories of grief: the mother whose son committed suicide, the spouses who were denied access to their loved ones at hospitals, the abuse in schools, the friend who was ostracized and blamed for their child’s transgender identity. Grief testifies to love, and most people understand and soften to love.

Also, I was surprised that you didn’t mention the arranged marriage plot, which did have a climax in the female characters saying no means no. Their story is of learning to stand up to the system, and how that kind of strength scares their enemy, even though it does not necessarily deliver them from their situation.

Ooph, sorry for the essay, Mouse. I got started and then my thoughts started coming together and then I just kept on going.

You think I’m one to talk?

I agree with this

* sees the end of the post *

YES! I can’t wait to see your review of the Star Wars miniseries! Are you gonna watch the CGI show as well?

I’ve watched it, sure. If someone asks I’ll review it.

To explain the story-within-a-story, I think Tuppence did a good job explaining its subversive elements. The problem is that that doesn’t make the characters seem less passive. The ego centrism that comes with active characters IS a problem, and it IS something that more stories should try to dissect. But the problem is that it’s hard to feel much for characters who have to be passive (or at least to some extent) given their position in history. I don’t have as much of a problem with passive characters because I grew up on fairy tales, but given your thoughts on Fantasia, I suspect you’re someone who really needs that connection and high level motivation in order to make a story work.